WAR STORIES — “Captain” Mansfield and his wife gather with unidentified guests at their home on Lake Monroe.

The steady influx of settlers into Florida was sufficient enough in 1823 for some of the lands in St. Johns County, including those within the boundaries of present-day Volusia County, to be split off and organized into what was named Mosquito County.

This widely despised name would remain in place until 1845, when lands that today include Orange, Brevard and Volusia counties were combined to form the much more appealingly named Orange County.

Most of the land along the St. Johns River, however, remained relatively undeveloped, with only a handful of small farms.

In 1822, one visitor wrote of encountering a settlement situated on “a very fine tract, lying on both sides of the St John’s [sic], the greater portion being on the western side of the river.”

The settlement had been formed four years earlier by Horatio S. Dexter, a Rhode Island merchant and adventurer. He had received a land grant of 2,000 acres and named his settlement Volusia.

Dexter’s interest in Florida probably began in connection with the Indian trade. He was issued an official license to do this in 1822.

Dexter then acquired nearby land suitable for cotton and sugar cane cultivation. The landing at Volusia became the regional shipping hub for exporting these crops.

Another name associated with this area during these early territorial years was that of Joseph Woodruff, who, in 1823, purchased 2,020 acres from an old Spanish Land Grant and established a plantation called Spring Garden.

Seminole War

The year 1835 brought a disaster that would reverse all the previous growth in Central Florida.

Increasingly harsh national policies of Indian removal culminated that year in the Seminole tribe being asked to sign yet another treaty that not only broke a string of previous treaties promising government land offerings, but also demanded that the tribe immediately remove themselves to Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

In effect, the treaty forced the dispossessed people to be collaborators in their own dispossession.

Some of the tribe’s chiefs felt they had no choice other than to comply, but the fiery warrior Osceola had had enough.

Legend has it that at the formal treaty-signing ceremony, Osceola shocked government and military attendees when he slammed his dagger into the document and declared: “The only treaty I will execute is this!”

It was the opening salvo in the Second Seminole War, which would become the longest and bloodiest of this country’s three armed conflicts with the Seminole Nation.

SEMINOLE WAR VET — Pictured is “Captain” Mansfield, who lived on the shore of Lake Monroe with his family. Mansfield, a veteran of the Seminole War and of the War of the Rebellion, was fond of telling war stories.

The flames of war spread swiftly over much of Florida territory. Despite being formidably outnumbered, the Seminoles were able, through guerrilla tactics, to fight U.S. military forces to a standstill in battle after battle.

One warrior in particular, Coacoochee, known to the settlers as “Wild Cat,” was largely responsible for extending the war by several years.

He took part in almost every clash of any importance, including one that occurred in West Volusia in late December of 1835 when Orlando Rees’ Spring Garden Plantation was attacked by Seminoles who burned down all the buildings, including the mill, and captured the slaves and livestock.

There never was a decisive battle that marked the end of the Second Seminole War. Fighting simply ground to a close in 1842, when there were not enough warriors left to sustain the fight.

In what essentially was a war of attrition, most of the Seminoles were killed or captured and relocated to Indian Territory in Oklahoma, although a remnant eluded forcible removal, and fled to the Everglades.

No peace treaty was ever signed, and no terms of surrender were ever formulated.

That the Seminoles were able to hold out for seven years demonstrates that their fight to stay in their homeland was “as gallant as any in history,” according to a noted Florida historian.

War’s impact on the region

The impact of the Second Seminole War on this region could not have been more devastating.

A widely circulated national publication described the extent of the destruction: “The whole territory south of St. Augustine has been laid waste and not a building of any value was left standing. There is not a single house now remaining between this City and Cape Florida, a distance of 250 miles.”

The already sparse population fled northward, and the 1840 census listed military personnel as the only inhabitants of the county.

The war was not without its advantageous outcomes, however.

Up and down the St. Johns River, several forts were established, each located at a primary intersection of the many roads that had been cut to provide access for transporting troops and supplies. These forts included Fort Barnwell and Fort Butler at Volusia Landing.

Nearly 3,000 miles of improved pathway were created, and several of them extended across what is now West Volusia.

In addition, surveyors laying out the plans for these roads were reporting that good lands for potential settlement could be found there.

In 1842, to encourage settlers to populate the territory, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act.

This law granted 160-acre tracts of land to any family who would move into the former battle zone, clear and cultivate 5 acres of the property, and build a house on it within the first year.

Another condition was that the land had to be 2 or more miles from a military post, and the applicant had to promise to resist raids from any of the scattered remnants of the Seminoles for a period of five years.

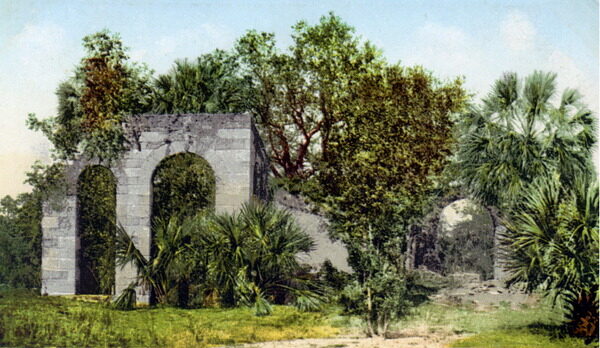

DESTROYED IN WAR — Shown are ruins of a sugar mill at 600 Old Mission Road in New Smyrna Beach. Built sometime between 1825 and 1835, it was destroyed by Seminole Indians during the Second Seminole War in the 1830s. Sometimes mistaken for a mission, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

With the settlers now required by law to bear arms for their own protection, a ready-made army was available in the event of any future conflicts.

New residents, and some returning ones, began to trickle into Central Florida, although few homesteads were recorded in the present-day DeLand area.

As their numbers increased throughout the region, the settlers, along with outside land developers, began to press for statehood.

Maintaining a balance between the number of free and slave states represented in the U.S. Congress was of paramount importance if the Union was to be preserved, so new states were admitted in pairs.

Florida was admitted to the Union as a slave state in 1845, and Iowa was admitted as a free state shortly thereafter.

Abolition and loss of profit

If the abolitionist policies of the Republican Party gained sway in Washington, the plantation owners’ great profit-making engine would be wiped out.

Yet the united, Northern-based Republicans were able to garner enough electoral votes over the deeply divided Northern and Southern factions of the Democrats in 1860 to put their first successful presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, into the White House.

— Ryder and her husband, Bob Wetton, live in DeLand and are active members of the West Volusia Historical Society. For information about obtaining a copy of her book Better Country Beyond, call the Historical Society at 386-740-6813, or email delandhouse@msn.com.

enjoyed your story,my grand father was ed stone,sherriff of vol.cty.